Inspiration for Differentiation

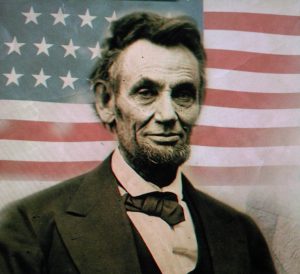

I’ve been slogging thru Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln as of late. It’s a refreshing read from most of what I surround myself with, though the heft of the work leaves me wondering what year I will reach the end. I have a habit of not finishing books.

However, I reached for Team of Rivals – after a respite of a month or so – and was again seduced by the quick pace of narrative, and the fascinating journey of our 16th President. Time and time again I find myself surprised at the maturity Lincoln exudes as he comes into his own. His sense of self, or rather, his differentiation of self, offers a wonderful mirror to reflect upon, a model to consider emulating.

Consider the following anecdote:

Lincoln, a lawyer previous to his career as a politician, was tapped on the shoulder to represent a major patent case, originally intended to be argued in Chicago. However, the case was relocated to Cincinnati, and another lawyer by the name of Stanton was asked to take Lincoln’s stead. Lincoln, uninformed about this change of representation, continued his preparations and showed up to court in Cincinnati none the wiser. Upon his arrival, Lincoln found himself not needed and his efforts unacknowledged nor considered. He was dismissed rather abruptly. Rather than retreat and return to Illinois to his office, Lincoln decided to stay and hear the case. His presence got under the skin of Stanton, his replacement, who was bothered by this “damned long-armed creature” hanging around, questioning Lincoln’s ability to comprehend the complexities of the case.

Lincoln found Stanton’s arguments not only compelling and convincing, but mesmerizing and inspiring. At the conclusion of the hearing, Lincoln vowed to return home and study law as though he had never studied it before, committing himself to the high standard before his very eyes.

Though Stanton refused to acknowledge Lincoln during the week-long hearing – indeed, Lincoln shadowed Stanton and his fellow counsel nearly every evening for dinner at a nearby restaurant, and walked practically alongside Stanton in public spaces while Stanton ignored him – Lincoln was in deep admiration over Stanton’s labor in the case. Painful as it was for Lincoln to not be granted victory in the court, nor even to have his own work glanced at by presenting counsel, Lincoln recognized the genius before him.

So great was Lincoln’s admiration for Stanton’s legal mind that, when elected President, Lincoln appointed Stanton Secretary of War. Soon his former opponent would become his greatest advisor and very dear friend.

Lincoln’s ability to rise above the not-insignificant-experience of being not only replaced but overlooked as a lawyer served him well as President. His maturity to separate the painful blow to his ego from his call to serve his country (and therefore call others to serve) bears witness to his capability for differentiation.